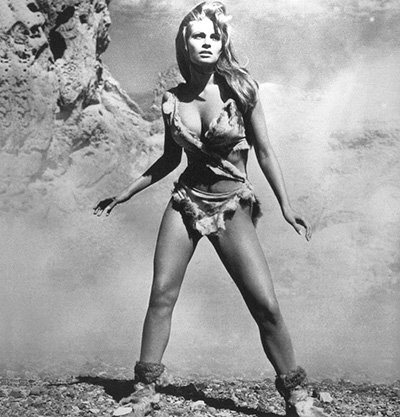

The future Kim Novak was born Marilyn Novak in 1933, in Chicago. A teenage model, Novak entered a few beauty contests, but she was hardly eyes-on-the-prize about it. She worked all manner of after-school odd jobs — dental assistant, dime store clerk, elevator operator. When she was 20, she earned the role of Miss Deepfreeze, and embarked on a national tour posing with refrigerators. The last stop was San Francisco, and the night before Novak was supposed to hop a train back east, a fellow model convinced Novak to come with her to Los Angeles for some R & R. When they had blown the $500 they had each saved seductively opening iceboxes, then they could go back to frozen Chicago. They had one goal: to swim in the Beverly Hills Hotel pool.

After about a month of lounging in the sun, the model friend did indeed go home. But Marilyn Novak stayed behind. She signed up with a local modeling agency, and they regularly found work for her as a movie extra, despite the fact that she was, as they frequently reminded her, carrying an extra 25 pounds.

Marilyn Novak’s big break came on the set of a Jane Russell film, The French Line. Jane Russell was a big star — literally, physically larger than the norm — and she looked particularly giant working it in front of a line of typically petite chorus girls. So director Lloyd Bacon issued a call for plumper potential background girls, and Marilyn Novak got the job. On set, she was spotted by Whit Melnick, a big shot agent who told her that if she could only lose 25 pounds, she could start making some real money in the movies — like $30 a week.

She did lose some weight, but she didn’t pursue Melnick’s offer. She wasn’t that interested in being a star. She really thought she was just biding her time until some guy came a long and married her and took her back to the Midwest and made a mom out of her. Melnick and a Columbia exec named Max Arnow had to almost force her to do a screen test.

The test was directed by Richard Quine, who would later direct Novak in Bell, Book and Candle (the two were engaged for awhile, but never married). Quine made Novak do the test while wearing an old strapless dress that had been worn in the movie Gilda by Rita Hayworth — the Columbia star whose refusal to work had created the vacancy for which Novak was being considered.

Novak signed with Columbia in 1953, the last of the contract stars. Harry Cohn was the head of the studio, and it wasn’t an exaggeration to compare him to a dictator — in fact, legend has it, he kept a framed photo on his desk of Mussolini. Harry Cohn made Marilyn her change her name because in the branding universe of Hollywood, there couldn’t be two Marilyns. So right from the start, she had to become someone different in order to stand out on her own. Cohn wanted to transform Marilyn Novak into someone called Kit Marlowe; the actress’ first act of defiance was to resist this, to insist on keeping her family name and to refuse to take on a first name meant to evoke a kitten.

But she wasn’t able to stop the studio from changing her look. Her weight was a constant battle. “That Fat Pollack,” Cohn called her, even though he knew fully well that Novak was of Checkoslovakian descent. Her teeth were capped, and her hair was bleached and rinsed lavender — a publicist had come up with the idea while flipping through Vogue, declaring that Novak’s life would be shaped into a “mauve symphony.”

All this embellishment and transformation made Novak understandably paranoid about her looks. She’d often hide in her trailer, paralyzed by the fear that her hair and makeup weren’t quite right or ready.

It didn’t help matters that Harry Cohn controlled his property —i.e.: his stars — through threats, frequently reminding his on-camera chattel that he made them, and he could break them. Stars were taught to fear what would happen if they stepped out of line. As they were being put on pedestals in public, behind the scenes they were cut down to size, their confidence eroded until they believed thatthey needed the support of the studio just to hold on to whatever security they had in the world. That they could barely live, let alone thrive, on their own.

It’s harder to control someone through intimidation and by hitting them in their inferiority complexes once they’ve become a hot commodity. Within three years of arriving in Hollywood, Kim Novak had become the hottest commodity. It was a one-two-three punch that did the job: she helped Frank Sinatra kick heroin in The Man With The Golden Arm; dancing in lust-zonked, post-war-conformity-smashing bliss with William Holden in Picnic; and, in the musical Pal Joey, she played the good girl side of a virgin-whore triangle with gold digger Sinatra and stripper-turned-society matron Rita Hayworth. Hayworth was 39. Her face already showing the impact of alcoholism, and she was trying to mount a post-third-divorce comeback. She was also, of course, the star Novak had been recruited to replace. Think of Pal Joey as the moment when the torch is passé from one generation of stars — Hayworth’s — to the next: Novak’s. Unfortunately Novak wouldn’t be able to hold on to the torch for very long.

But it was good while it lasted. Across this run, Novak’s movies earned nearly ten times their production budgets. Kim Novak sold more tickets than John Wayne, Doris Day and Marilyn Monroe — the woman who indirectly gave Kim her name — combined. And she became so valuable to Harry Cohn and Columbia that they would be forced to overlook when she’d say something a little too candid in the press, or perhaps go out at night with the wrong kind of guy.

What’s to account for her sudden, massive popularity? What was she broadcasting in the mid-to-late 1950s that audiences so fervently responded to?

“It’s strange, because she didn’t have a sharply defined personality,” says Nehme, “Like Shirley MacLaine being kind of kooky, or Marilyn’s vulnerability coupled with the dumb blonde image she was shackled to, or Grace Kelly being the epitome of high class. Novak was almost defined by what she wasn’t. She wasn’t really any of those.”

Novak brought something unique to the screen. She was the master of the almost-blank, enigmatic stare. Maybe it’s crazy hyperbolic to call Novak the female James Dean, but there’s something to the comparison. There’s a real angst to her screen presence, a kind of petulant pain that you don’t get from many actresses of her day. Just as Dean’s three screen performances, when taken together, encapsulate something tangible about being a young man in the 1950s, so too do Novak’s handful of really interesting performances give face and body to the repressed agony of being a young woman in the 50s.

“There’s something very 50s about Novak,” Nehme confirms, “because the surface is incredible, but you get a sense that there’s a facade. And that feels very Eisenhower, doesn’t it? That you’ve got this perfect surface, and then in back, there’s this mess of things that need to be worked on.”

She may have been molded after Marilyn and groomed to replace Rita, but unlike the pin-ups that preceded her, Kim Novak rarely seemed to be having fun with her sexuality. If anything, she made being stuck in a beautiful body seem like an unconscionable burden.

Of course, a lot of that had to do with what she was asked to do. In each of her three big hits between 1955 and 1957, Novak played a gold-hearted bombshell whose outsized sexual appeal causes some kind of panic. But these girl-women are hardly in control of their powers—in fact, they’re all wounded birds in thrall to charismatic bad news boyfriends — Sinatra’s Golden Arm junkie and Pal Joey hustler, William Holden’s chiseled vagabond whose presence at a small town Picnic inspires hysteria. Novak’s characters clung to these damaged bachelors as though they had absolutely no other options. And maybe they didn’t. Over and over again, Novak’s characters are told their beauty and their bodies are their only source of value, and then they’re humiliated for trying to assert any kind of ownership over their assets.

Think about this scene from Picnic, in which Novak, playing 19 year-old small town beauty Madge, is pressured by her mom into using her feminine wiles to land a rich husband — whether she likes him or not:

Mom: “When a girl’s as pretty as you are, she doesn’t have to—“

Madge: “Oh mom! What good is it to just be pretty?”

Mom: “What a question!”

Madge: “Maybe I get tired of only being looked at.”

Mom: “You puzzle me when you talk like that…Madge, does Alan ever make love?”

Madge: “Sometimes we park the car by the river.”

Mom: “Do you let him kiss you? After all, you’ve been going together all summer…”

Madge: “Of course I let him!”

Mom: “Does…does he ever want to go beyond kissing?”

Madge: “Oh, Mom!”

Mom: “Well, I’m your mother for heaven’s sake…these things have to be talked about! Do you like it when he kisses you?”

Madge: “Yes.” [As in, “duh!”]

Mom: “You don’t sound very enthusiastic?”

Madge: “Well, what do you expect me to do? Pass out every time Alan puts his arms around me?”

Mom: “No, you don’t have to pass out. But there won’t be many more opportunities like the picnic tonight, and it seem to me you could at least -“

Madge: “What?!?” [The clear implicationis that her mom is telling her to put out so as to ensure bagging this rich husband.]

Mom: “Oh! [Exasperated] Nothing!

In her personal life, too, Novak was expected to at least pretend to be a certain type of girl, and only be seen with the right types of men. But by 1957, she was so fed up with all the rules imposed on her that she either stopped caring about conformity, or actively chose to rebel against it.

At a party at Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh’s house that year, Kim Novak met Sammy Davis Jr. At that time, three years after the car accident in which he lost his left eye, Sammy had already triumphed on Broadway in Mr. Wonderful, but the Rat Pack wasn’t really a thing yet, and in unquestionably racist Hollywood, real movie stardom was proving elusive. Both Kim and Sammy struggled to conform to what was expected of them based on how they looked, and both felt like outsiders on the inside. The two were instantly attracted to one another, and spent the whole night deep in one-on-one conversation.

The next day, after their meeting had made the tabloid news, Sammy called Kim to apologize—he knew the very idea that Novak had allowed herself to be chatted up by a black man in public would send Harry Cohn into fits. “The studio doesn’t own me!” Kim responded, and invited Sammy over to her place for dinner. So began a series of clandestine dates. The two eventually rented a house in Malibu for their rendezvous, but they couldn’t be too careful: Sammy still felt the need to lie on the floor of his chauffeured car, covered up by a blanket, so that no one could see him in transit and connect him to Novak. This wasn’t pure paranoia: from the moment Novak signed her contract, Columbia had private detectives on her tail.

Kim Novak was playing out this duplicitous chapter in her private life through the back half of 1957, which means it must have overlapped with the making of her masterpiece, Vertigo.

Novak felt a special connection to the material. Maybe she was uniquely inspired by the Vertigo script to start taking back her own identity; maybe she was emboldened by the secret she was keeping in her personal life. Regardless: Kim Novak chose this moment to start fighting back. In September of ’57 Novak famously held up the start of production on Vertigo, refusing to show up to work at Paramount, to which she had been loaned out, until Harry Cohn at Columbia renegotiated her contract. It was a huge gamble, but it paid off: The studio caved, and despite a brief skirmish over her wardrobe — Novak initially resisted wearing the black spike heels and form-fitting grey suit that Hitchcock had transposed into the script direct from his own fantasies — the making Vertigo was, by Hitchcock standards, relatively painless.

The trouble was soon to come. Novak’s work on the movie was done by December 1957, when she went home to Chicago to spend Christmas with her parents. By that point, the affair with Sammy had apparently hit levels of delirium — at least, for him. Booked to do a series of shows at the Sands in Las Vegas, one night Sammy told the casino they’d have to find a replacement - and then he hopped on a red eye to Chicago, determined to meet Kim’s parents and ask for their daughter’s hand in marriage. He was barely on the ground in Chicago before he had to turn around and fly right back, so as to be in Vegas for that night’s show.

It was totally nuts, the kind of lovestruck madness that only happens in movies — and apparently, to people who make movies. And it backfired: reporters in Vegas noted Sammy’s absence and put two and two together, soon word reached Harry Cohn in New York of the impending scandal about to break in magazines like Confidential. Cohn called his assistant, Max Arnow, in LA, to inform him they had a disaster on their hands.

The damage control process began, but Cohn and Columbia weren’t able to move fast enough: two hours later, the first blind item about an affair between a certain K.N. And S.D hit the New York papers. Harry Cohn had his first heart attack the next morning. Over the next weeks, gossips dispensed with the discretion. “Kim Novak is about to become engaged to Sammy Davis Jr,” announced the London Daily Mirror, “and Hollywood is aghast!” Confidential called it “the tragic love story of the century,” and claimed Frank Sinatra had told his friend and Vegas co-star, “Sammy, you’re making a serious mistake.”

At this point, enough was enough. Legend has it that Harry Cohn hired gangsters to drive Sammy Davis Jr out into the desert. Not to seriously hurt the guy, just to put the fear into him, so he got the message that the Novak affair had to be called off. But Sammy had mob ties of his own, who could keep him safe as long as he stayed in Vegas. Eventually, Cohn’s mobsters and Davis’ mobsters worked out a deal: since the only surefire way to kill the story was to change the subject, Sammy would have to marry someone else. He’d have to give up the beautiful blonde top box office draw in Hollywood, and hook up with someone…more…appropriate. Someone like Loray White, a single mom and chorus girl whom Davis had dated a couple of times. No one was under any illusions that this was romantic matrimony: White signed a contract stipulating a $25,000 rate for one year of marriage.

The scandal was thus put to bed, but on some significant level, the principles never fully recovered. Sammy Davis went to his death bed vowing that Kim Novak had been the love of his life. Harry Cohn’s wife believed the scandal killed him; two months after the heart attack he suffered amidst the first gossip reports, he was dead. Novak quickly bounced back in her romantic life — in fact the promotion of Vertigo was marred by a scandal involving the gifts she allegedly received from her alleged new boyfriend, the son of the prime minister of the Dominican Republic— but without Cohn around to guide her selection of roles, she struggled. Vertigo’s lackluster box office performance broke Novak’s lucky streak. Aside from Quine’s Strangers When We Meet and Billy Wilder’s fascinatingly vulgar Kiss Me Stupid — in which Kim starred opposite one of Sammy’s Rat Pack cronies, Dean Martin — the next few years brought on a string of duds.

Then, in 1966, Novak’s LA home was endangered by mudslides. She had managed to fill a station wagon with valuables, furniture and paintings and such, and was taking a final armful of things to the car when she looked up and saw that journalists were starting to gather in her driveway—a handful of newspaper men, and a truck from NBC. Shocked by their presence, she dropped a sculpture, which smashed to the ground. Her eyes swelled with tears, and she according to one of her biographers, right then and there she vowed, “I’m getting out of Hollywood. And I won’t come back — ever!”

She did leave Los Angeles, moving first to Big Sur and then, after marrying veterinarian Bob Malloy in 1976, up to his ranch in Oregon. It took her another 25 years to officially stop working, although there’s not much on her filmography of note after 1968, when she starred in Robert Aldrich’s totally loony The Legend of Lylah Clare.

A kind of end-of-the-Hays-code-sploitation thriller-cum-camp remake of Vertigo, Lylah Clare cast Novak as a mousey girl who’s essentially forced to star in a megalomaniac director’s movie as the dead, Marlene Dietrich-esque bi-sexual star whom he loved and whom she resembles. The Legend of Lylah Clare has been virtually forgotten, and for fairly good reason, although once again, it gave Novak a chance to rehearse her own real-life struggles to assert herself in an industry that routinely dehumanized her — and it did so in much more vulgar terms than Vertigo.

If the question sparked by the Oscars was, “What happened to Kim Novak?” well, here’s what we know. She worked the tribute circuit in the late 90s, when Vertigo was restored and rereleased, and then largely slipped out of the public eye for the next 15 years, popping up for the occasional interview or film festival. In 2006, she had a serious horse riding accident, suffering broken ribs, a punctured lung and nerve damage. Then, four years later, she was diagnosed with breast cancer.

Just two years ago, she appeared on stage a few doors down from the Dolby Theater, in a conversation with Robert Osbourne that was later aired on TCM. In that conversation, she admitted to having been diagnosed as bipolar, and cried talking about the production of her final film, Liebstram, directed by Mike Figgis. It’s possible some of her changed appearance could owe to these very real health problems. It’s also possible that after an entire life of being told that she had to be made over in order to be accepted in Hollywood, she internalized the mandate to transform herself. We all know defying nature is a slippery slope. We learned that from the movies.

“Any reminder of your imperfections is just magnified in your brain, and I had always found that really sympathetic about Kim Novak,” Nehme says. “And so, especially the day after the Oscars, I was so indignant that people were going after her! I was just like, ‘Don’t you know that she’s always been insecure?!?”

After she wrote her blog post about Novak, Farran was tipped off by a reader, the writer Dan Callahan, to an interview Novak gave last October, in which she acknowledged that she had gone to see a plastic surgeon — and regretted it:

“She wanted a fresh look but ‘I didn’t want to do anything major.’ A doctor suggested fat injections to add fullness to her face. She said, ‘That was absolutely crazy when I think about it now. You spend all your time trying to get rid of fat. I love the kind of hollow cheekbone look,’ Novak says. ‘So Why did I do it? I trusted somebody doing what I thought they knew how to do best. I should have known better. But what do you do? We do some stupid things in our lives. I mean, you pay to look worse? You pay money for that?’”

We know Hollywood is tough place for aging actresses. We know most of them end up doing something artificial in order to stall the aging process or to foster the illusion of eternal youth and beauty. So why did Novak’s altered appearance cause such an uproar? Maybe it’s because her whole career seems to have been defined by that push and pull, between wanting to be appreciated “for who she was, for herself,” and the pressure to conform to an imaginary ideal, or just straight up transform into someone else. Or maybe, it’s because it seems to go against the one thing that, at her peak in the 1950s, made Novak really stand out.

“On the one hand, she’s got this very dramatic beauty,” Nehme says, “But…I watch Audrey Hepburn and Grace Kelly, who were also big stars in that period, or even sophia Loren, and they’re so beyond mortal women. But you look at Kim Novak and there’s something relatable about her. It’s a rare quality to a screen beauty, that you look at her and say, ‘There’s a reality to her, and how she’s dealing with her beauty.’”

One final note: While Novak has frequently acknowledged that Harry Cohn forbid her from being seen with Sammy Davis Jr., she’s never publicly acknowledged that her close friendship with Sammy, as she’s called it, was sexual. Maybe the sheer fact that we expect famous women to disclose details of their sex life is part of the problem.