Listen to this epsiode on Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

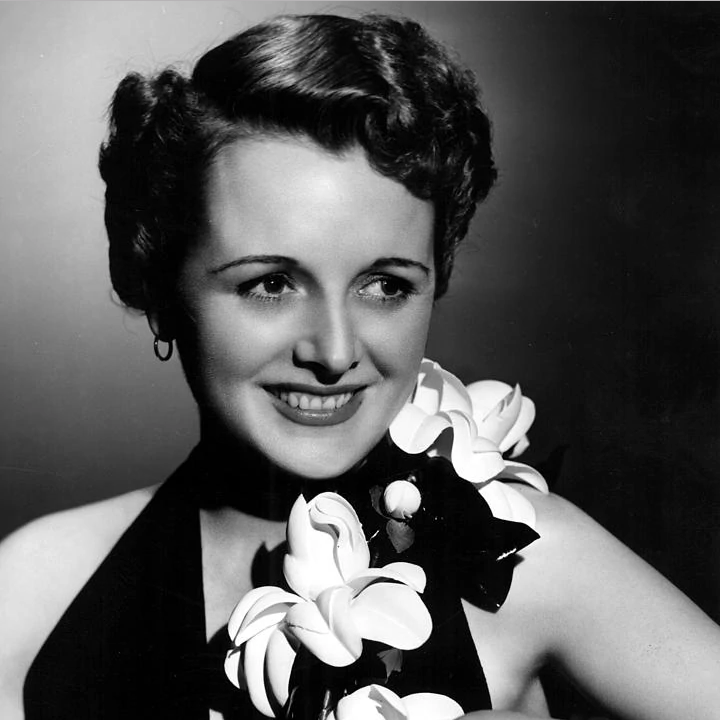

Mexican actress Lupe Velez was the victim of one of Anger’s cruelest invented stories. His fabrication of her manner of death lays bare a vicious racism in addition to Hollywood Babylon’s usual sexism. Today we will sort out the fact of Velez’s life from Anger’s fiction, and consider the star of the Mexican Spitfire series as comedienne ahead of her time.

SHOW NOTES:

Sources:

Hollywood Babylon by Kenneth Anger

Lupe Vélez: The Life and Career of Hollywood’s “Mexican Spitfire” by Michelle Vogel

“The Turbulent Life and Tragic Death of “Mexican Spitfire” Lupe Velez” by Hadley Meares, Los Angeles Magazine, February 8, 2018

“Lupe Vélez: The Tragic Tale of a Femme Fatale” by Laura Havlin, anothermag.com, July 16, 2015

“Dolores del Río and Lupe Vélez: Working in Hollywood, 1924-1944” by Clara E. Rodríguez

“Lupe Velez: Early Hollywood path-paver by Susan King, Los Angeles Times, August 13, 2012

“Johnny’s ‘Bad Habits’ Win Divorce for Talkative Lupe” The Akron Beacon Journal,

August 16, 1938

“Lupe Velez and her Tarzan Finally End Squabbling With Real Divorce” Nevada State Journal,

August 16, 1938

“Lupe Velez Tempestuous Romance with Tarzan is Finally Ended” The Morning Call, August 16, 1938

“Lupe Velez Wins Her Second Divorce” The Philadelphia Inquirer, August 16, 1938

Music:

The music used in this episode, with the exception of the intro and outro, was sourced from royalty-free music libraries and licensed music collections. The intro includes a clip from the film Casablanca. The outro song this week is “Spanish Eyes” by Madonna.

Excerpts from the following songs were used throughout the episode:

Southern Flavors 3 - Martin Gauffin

Club Noir 2 - John Allen

Come Over To Me - Tommy Ljungberg

One Two Three 5 - Peter Sandberg

Yellow Leaves 5 - Peter Sandberg

Latin Passion - Håkan Eriksson

Amor De Danca 3 - Martin Carlberg

El Que Quiera Bailar 2 - Martin Landh

Unsolved - Mythical Score Society

Neblina 4 - Anders Göransson

A Time To Remember 3 - Martin Landh

Eventually Maybe - Oakwood Station

Credits:

This episode was written, narrated and produced by Karina Longworth.

Editor: Cameron Drews.

Research and production assistant: Lindsey D. Schoenholtz.

Social media assistant: Brendan Whalen.

Logo design: Teddy Blanks.